They say cooking is a science. As is often the case with scientific discoveries, not all of them are planned…

I enjoy a little experimentation in the kitchen – usually in the form of trying out different recipes, hunting for new ingredients or cultivating bacteria to create various fermented treats. All of these experiments share a core thread: they are planned. They are things I intend to do, and I enjoy doing them.

One thing I did not intend to do (and did not know was possible) was to create a small electrical current in my fridge by marinating a leg of lamb. I cannot say this brought me much enjoyment, but it has subsequently turned into quite an interesting science lesson – one which I hope you’ll find as interesting as I do.

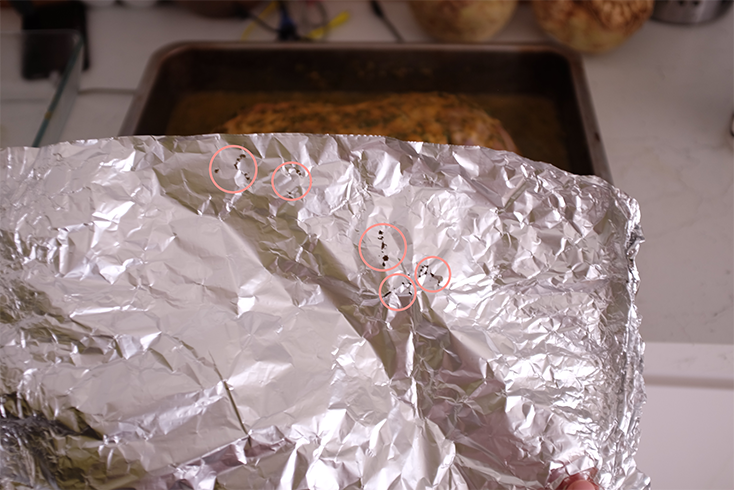

Having prepared my lamb by rubbing it with a mixture of spices, herbs, oil and lemon juice, I left it covered in aluminum foil in the fridge overnight. By the next morning there were small holes in the foil that looked like they had been burned into it. I had absolutely no idea how they got there – perhaps the citric acid in the lemon juice? But I was clutching at straws.

Consulting the internet brought up a small collection of people complaining of a similar problem, all as confused as I was about their situation. The resounding answer to our collective culinary confusion was direct, but prompted more questions than it answered: we had all unwittingly made ‘lasagne batteries’.

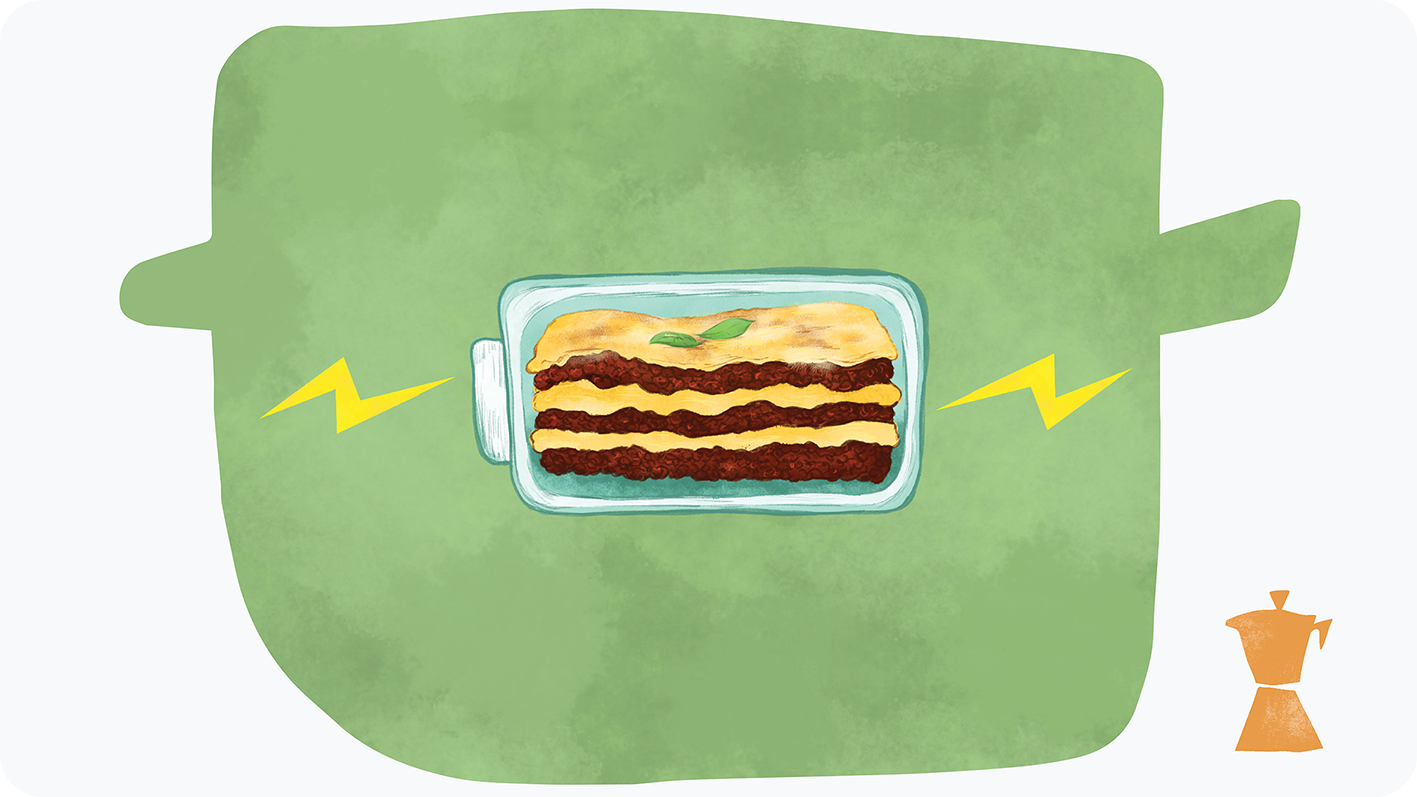

What is a ‘lasagne battery’?

This is the obvious first question – quickly followed by how I managed to create one without even making a lasagne.

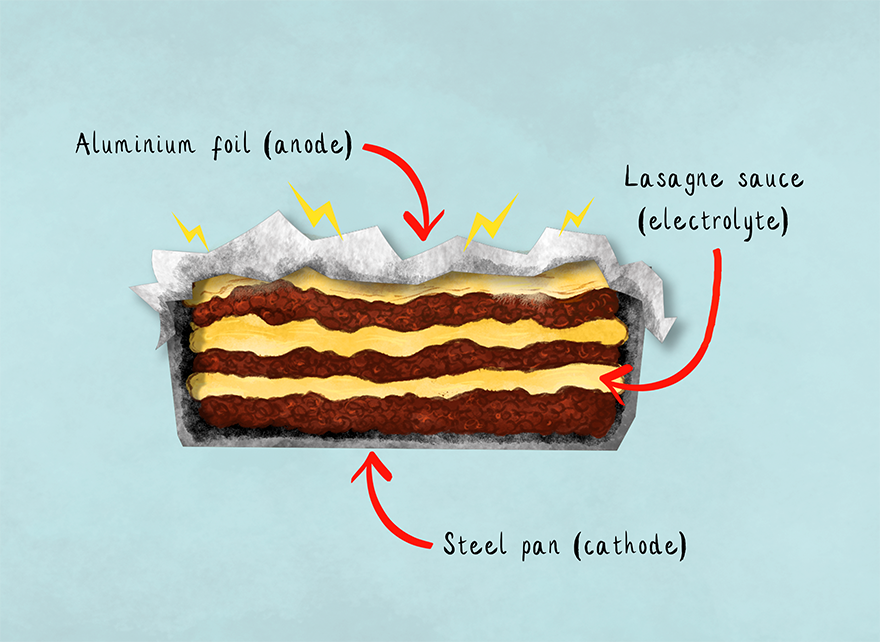

As a quick recap for anyone who (like me) has forgotten their school chemistry lessons, a battery is formed of three things: an anode (positively charged), a cathode (negatively charged) and an electrolyte (a substance that allows charged ions to move between the two). It turns out if you want to make such a thing in your kitchen, it all comes down to the pan you use.

The reason for the name ‘lasagne battery’ (or ‘lasagne cell’) is that it’s fairly common for a lasagne to be made in a steel tray and then stored to eat later under aluminium foil – and even cooked with the foil on. In this arrangement the two different metals (steel and aluminium) function as an anode and a cathode, and the tomato sauce (containing acid from the tomatoes and charged ions such as salt) becomes the electrolyte. As a result a small electrical current is produced, which causes ions to move away from the aluminium foil and cause the burned-hole effect I witnessed in the case of my marinade. This ‘pitting’ effect is in fact an example of galvanic corrosion – sounds tasty, right?

This means that this form of culinary electricity generation does not require a lasagne, but it is the most common food with which this is achieved. Lasagnes also produce the most obvious effects by the sheer amount of corrosion, given the surface area of a lasagne which will be in contact with the foil.

In my case I had placed my soon-to-be delicious marinating lamb leg in a steel pan, and then covered this in aluminium foil. It turns out I was right to have suspected the lemon juice, but rather than the citric acid burning through the foil, it had in fact helped create an electrolyte so ions could start moving – just as happens with the tomato sauce in the case of a lasagne.

If you want to avoid making a ‘lasagne cell’ then all you need to do is use a ceramic or glass dish, or use a metal pan and cover with cling film instead of foil. You will not get this effect unless two different metals are: 1. present, 2. in contact with each other, and 3. In contact with an electrolyte.

Is it safe to eat?

I personally did not throw away an entire leg of lamb I had marinaded for 12 hours as per the instructions of Yottam Ottolenghi. After consulting with some friends I chose to scrape off the bits that had caused the ‘burns’ in the foil and to roast the lamb as planned.

I can happily report that myself and my dinner guests all survived the evening seemingly unscathed, giving me some reassurance that lasagne batteries are probably safer to eat than lithium ones.

However, I want to stress that I do not recommend this approach – and the evidence I have found suggests you should bin rather than eat anything that has become a battery in this way. Professor Greg Blonder puts it fairly succinctly: “you shouldn’t ingest gravy filled with metal ions”.

As life advice, it’s pretty hard to disagree with.

Can I power my house with lasagne?

This is the final question that comes to mind, but I am afraid the ‘lasagne battery’ is not a panacea to solve the cost of living crisis (a fact that will no doubt be felt hardest across the nation of Italy).

The flow of current you can get out of a well-made lasagne battery/poorly stored lasagne (depending on your perspective) is only going to get you enough charge to ruin some of your tin foil rather than put a dent in your electricity bill. Even the Wembley Lasagne would struggle to be energy efficient in this regard, unfortunately.

Overall the ‘lasagne battery’ is something best understood theoretically, and this knowledge is mainly useful to avoid making one yourself. Maybe some mad culinary scientist could do some further experiments to generate increased amounts of electricity from their dinner – such as this video of someone powering LED lightbulbs with tomatoes and potatoes.

For me, though, I’m happy to stick with my ferments and more traditional culinary experiments – and to avoid ingesting gravy filled with metal ions (cheers professor).

Cover illustration credit: Sneha Alexander