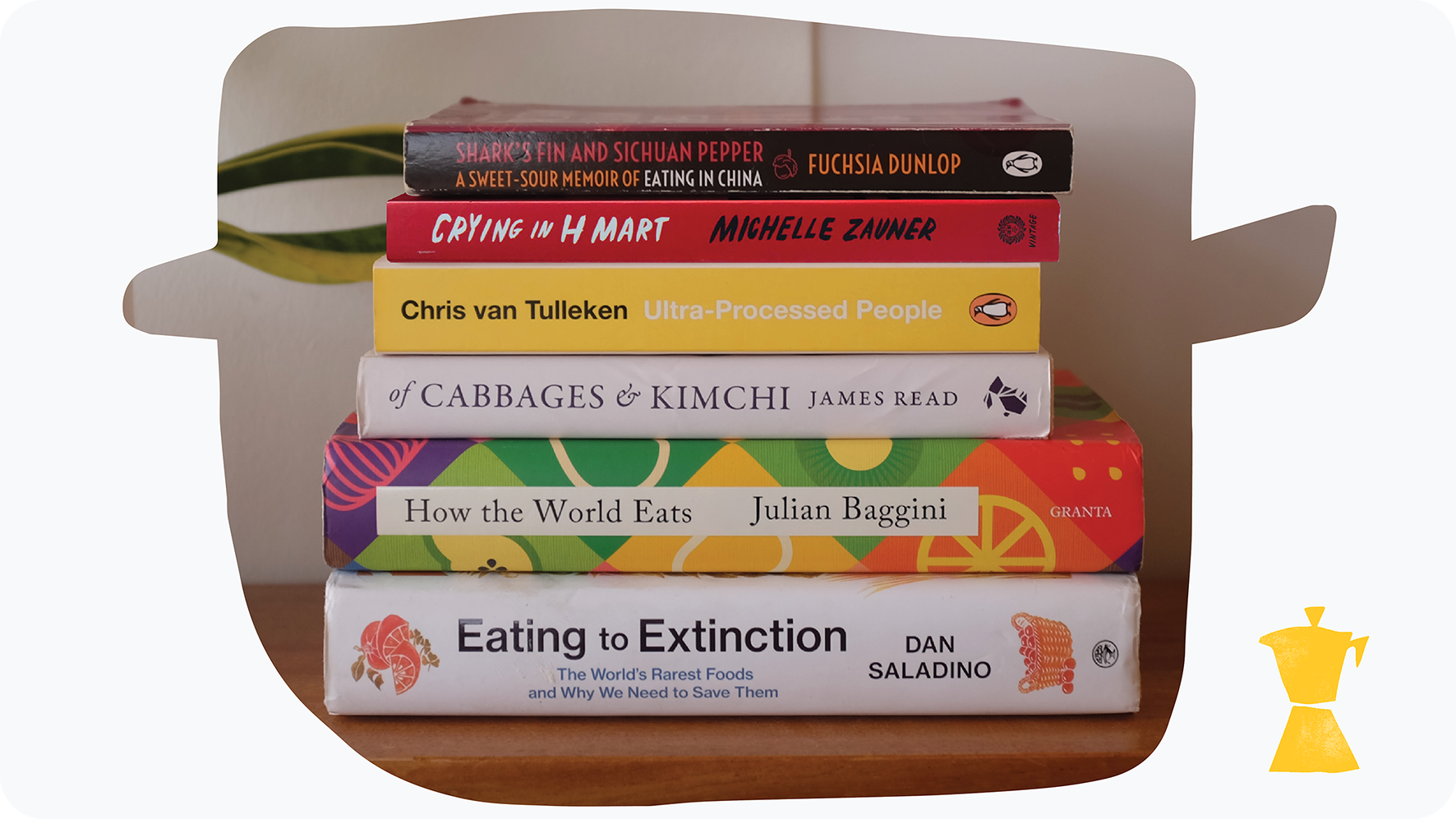

The six best books about food I read this year, and why I think they’re worth your time.

If you’re looking for your next read, I would highly recommend any of the following six books. As a quick point of clarification, what I mean here by a “food book” is a book that is in some way centred around food – either in terms of how to make or prepare certain dishes, explaining the processes by which food is produced or exploring one’s relationship to food as a deeper indicator of identity and belonging. Food is something that cuts through every aspect of life, and I wanted to reflect that diversity in the books I’m recommending.

What I like about the books in this list is that each of them changed the way I think about food. In different ways, all six explore our relationship with what we eat, the significant role culinary traditions play in our lives and what’s at stake if we start to lose our connection with the past.

Here’s the list, scroll down for why I found them so brilliant and why I’d recommend reading them:

My recommendations:

- Shark’s Fin Soup and Sichuan Pepper – Fuchsia Dunlop

- Of Cabbages and Kimchi – James Read

- Crying in H Mart – Michelle Zauner

- How the World Eats: A Global Food Philosophy – Julian Baggini

- Ultra-Processed People – Chris Van Tulleken

- Eating to Extinction – Dan Saladino

Shark’s Fin Soup and Sichuan Pepper (2011) – Fuchsia Dunlop

Shark’s Fin Soup and Sichuan Pepper is Fuchsia Dunlop’s memoir of living in Chengdu in the 1990s. Having originally traveled out on a British Council scholarship, Dunlop found herself falling in love with Sichuanese cuisine and decided to stay and study at the Sichuan Higher Institute of Cuisine – one of the first Westerners ever to do so. I read this because Fuchsia Dunlop’s The Food of Sichuan is one of my all-time favourite cookbooks, and the story it tells makes clear to me why Dunlop’s recipe books are so extraordinary.

The book’s stories from late-20th century China are peppered throughout with recipes (in particular I recommend the dan dan noodles and fish-fragrant aubergines) – but Shark’s Fin Soup and Sichuan Pepper is not a cookbook; it is a book about a culture that expresses itself through food. This is typical for Dunlop, who is most in her element when talking about food cultures and the ways in which different populations think about food in unique ways. She explains that what drew her to Sichuanese food was its unpretentious joy: how people in Chengdu approached what they ate with care and attention as the stuff of life, seeing food as something valuable in its own right – rather than as fuel or a vehicle for discussing business (as Dunlop sardonically identifies in Cantonese culinary culture).

What I found so brilliant about this book is that it illustrates the amount of learning you have to do in order to start to understand a food culture – and how there is so much more to making meals from different places than memorising a recipe. Before she can even pick up a knife, Dunlop has to immerse herself in the culture of Sichuan: learning not just the dialect but also how (and, crucially, what) to eat. The Sichuanese taste for volcanic levels of spice and willingness to eat every part of an animal are cultural signifiers that Dunlop has to (literally) consume into her identity before she can be taken seriously. This is most notably represented by the transformation of her initial disgust at eating spicy rabbit heads into delighting in them as a late-night snack.

Shark’s Fin Soup and Sichuan Pepper is in many respects a love story. A story about how a person became enchanted with a place, its people and their food – and how this changed the course of her life. There are very few books like it.

Of Cabbages and Kimchi (2023) – James Read

This is a fantastic and fun guide to the world of fermentation – with absolutely beautiful illustrations from Marija Tiurina giving a suitably alien-like beauty to the process. Over the last year I’ve been fermenting more things recently and really enjoying it – especially making kimchi, water kefir and sourdough. Through reading James Read’s recipes in Of Cabbages and Kimchi, I’m finding more and more doors being opened (and more and more jars being purchased).

The book takes you step-by-step through different kinds of fermentation, with each section starting with a very readable and engaging essay, before giving some recipes for you to try at home. What makes Of Cabbages and Kimchi so useful from a practical perspective is the way it gives an easy-to-understand explanation of why each process works, and the different bacteria involved. This means you aren’t just blindly following each recipe, but kind of carrying out experiments from a thoroughly enjoyable science textbook.

Among the practical advice you’ll also find countless wonderful pieces of information – such as Captain Cook managing to avoid scurvy among his crew by sailing with nine tonnes of sauerkraut aboard his ship, Lydon B Johnson funding research into canning technology to contain kimchi effectively and thus ensure the assistance of the Korean army in the Vietnam War, and that the original voice that said “you’ve been tangoed” in the famous 90s Tango ads was none other than Gil Scott-Heron!

So far from the recipes in this book I’ve made a soy caramel dark milk chocolate tart (which is incredible and almost unimaginably rich), a batch of soy pickled cucumbers (absolutely delicious as part of a japanese meal with rice), my own yoghurt (with the aid of a thermos flask), and I’m looking forward to continuing my experiments with a ginger bug…

Crying in H Mart (2021) – Michelle Zauner

Crying in H Mart explores the foundational role national cuisines play in creating collective identities – and what’s at stake on a personal level when one starts to feel that connection and knowledge slip away. It takes the form of a heart-wrenching memoir about Michelle Zauner’s mother dying of cancer, and is one of the most emotionally impactful books I’ve read in the past year (I would not recommend reading this on the bus).

Combined with the title, the book’s opening line, “Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart” immediately places Zauner’s grief in the context of an Americanised Korean experience – literally located in the US’s largest Asian grocery store. The shelves of H Mart, stocked with Korean ingredients, hold fragments of her mother’s identity; throughout the book we see Zauner desperately try to cling to these as she feels a fundamental rupture within herself.

Zauner tells the reader how, as the daughter of a white father and a Korean mother, “I relied on my mom for access to our Korean heritage. While she never actually taught me how to cook […] she did raise me with a distinctly Korean appetite.” Later, as her mother’s illness progresses, Zauner immediately knows the dishes she would like to make (the same ones her mum would make for her when Zauner was ill as a child), but she realises she doesn’t know how to make them. We watch on as Zauner starts to feel increasingly detached from her cultural identity, and the person who had always anchored her within it slips away before her eyes (as I said, do not read this on the bus).

There’s a bittersweetness that pervades the book. Zauner’s culinary exploits making kimchi and other Korean staples start to connect her to a culture she had previously assumed would simply be ever-present, but these moments of self-realisation and connection exist in the context of raw and unflinching depictions of the awful things cancer does to a human body.

It’s always a feat when a book tells you how it’s going to end, but this doesn’t lessen your curiosity or take away from its emotional impact. This is what Crying in H Mart achieves. It is a book specifically concerned with one person’s experience of grief, loss and belonging – and at the same time a meditation on fundamental parts of life that are relevant to anyone. I can’t recommend it enough.

How the World Eats: A Global Food Philosophy (2024) – Julian Baggini

If you’re looking for an accessible but rigorous examination of the global food system (and how we might fix it), this is the book you should read. As a philosopher who focuses primarily on personal identity, Baggini brings a revealing perspective on the role food plays in people’s lives and the moral, ethical and environmental problems posed by our interconnected world.

While he isn’t an expert on food, or at least wasn’t before starting work on this book, it’s clear Baggini has done his research. The book deftly guides the reader through the complex challenges facing our food systems before arriving at seven “pillars” upon which Baggini believes a better system could be built. Throughout this global food tour the text is punctuated with inputs from some of the most influential thinkers in food policy, such as Tim Lang, Marian Nestle and Gyorgy Scrinis – helping contribute to a brilliant overview of where we are currently at in terms of thinking about these problems, and why they’re so tricky to solve.

Given his background, it’s unsurprising that Baggini is at his strongest when examining specific issues within food systems through a philosophical lens. He’s unafraid to face difficult issues head on, such as whether the world could ever move to a more ethical way of farming crops such as cocoa, how to regulate GM crops effectively without stifling possibly life-saving innovations and how we should feel about the cruelty and suffering caused to animals around the world due to our decision to consume meat. Baggini’s ability to lay out the problems in plain English before realistically examining possible solutions is a fantastic aid to demonstrating just how difficult it is to figure out good interventions within food systems.

Of the seven “pillars” that Baggini arrives at, the ones that really stick with me are “resourcefulness” and “foodcentrism”. By the former of these, he means that we have to think about the best ways to manage our resources and not be too constrained by already-held beliefs: simplistic solutions from either a technophobic or technophilic perspective will not work; we can’t go live in the woods again, nor is it helpful to say we’ll live in The Matrix. We need to think about where we are and honestly assess the benefits and drawbacks of the tools and innovations available to us.

By “foodcentrism” he means that we have to approach the food system by actually thinking about food. This seems blindingly obvious, but I agree with Baggini that our current system is not necessarily pointed in this direction. So much activity in what we call “the food system” is geared more toward producing commodities for industrial production (e.g. corn to manufacture high fructose corn syrup) than foods designed to be consumed whole. Equally our ways of thinking about the food we consume are becoming increasingly scientific: nutrients and macros rather than ingredients and whole foods. If we don’t start with food at the centre, we’re never going to fix the problems we face.

Ultra-Processed People (2023) – Chris Van Tulleken

This is probably the book, out of everything I’ve ever read, that has had the single biggest impact on how I live my life. The way I often describe it to friends is that you can feel yourself becoming indoctrinated as you turn each page – as Van Tulleken makes an increasingly watertight case that ultra-processed food is a societal problem on an almost inconceivable scale, and it is a problem that is only getting worse.

The problems associated with UPFs are getting more and more attention in the public consciousness now, which is a good thing (because there are loads of them). Van Tulleken does a brilliant job taking the reader through Carlos Monteiro’s studies in Brazil which rang the first alarm bells about UPFs and established the NOVA classification system (which is used to classify food by level of processing). He also explains in plain language the dangers posed by our increasingly ultra-processed diets, not just in terms of the global health implications of rising rates of obesity and malnutrition, but the cultural damage wreaked as established food cultures are replaced with global UPF brands.

A point that Ultra-Processed People explores particularly well is the political and economic dimension of ultra-processed foods. UPFs are in many ways pure capitalist products: an ultra-processed burger or drink aims not to feed people or give them necessary nutrients, but purely to drive its own consumption. Tricks like being ‘pre-chewed’ (UPFs essentially disintegrate in your mouth with very little chewing required) or the adding of scent to ice cream packaging (when you smell caramel as you open the package, that’s from a chemical on the packet not the ice cream) are just a couple of ways in which big food companies psychologically manipulate people into desiring their food and consuming too much.

The essential point driven home by Van Tulleken is that UPF isn’t food. Instead it is an edible product flavoured to taste like food (in many countries in South America these foods are referred to as “ultra-processed products” for this reason). This has been a huge influence on me making more of my own food at home – including sourdough bread, granola, pasta and pesto – and to start studying for a master’s degree in Food Policy. Like I said, it’s had a fairly big impact on my life…

Eating to Extinction (2021) – Dan Saladino

Despite its rather imposing title, I found a lot more to be optimistic than pessimistic about when reading this wonderful book by Dan Saladino. Eating to Extinction is a well-researched and enjoyable collection of essays, each one about a part of the food system (a specific ingredient, plant, dish or drink) that is under threat. It’s a book which gives you an appreciation of the importance of diversity in the food system, and the ecological and cultural heritage that is at stake when we ignore the past or pretend we know better.

Reading Eating to Extinction gives you lots of delightfully surprising bits of information – such as the fact that the design of champagne bottles originated with producers of perry cider in rural England and that every apple in the world traces its roots back to the Tian Shan mountains in modern-day Kazakhstan. It also depicts how food can be prepared, stored and preserved in even the harshest climates, such as the dramatic conditions which are harnessed to make Skerpikjøt in the Faroe islands – a process whereby mutton is semi fermented by being strung up in deliberately drafty huts to be buffeted by strong, salty sea winds.

Throughout the book you see cultures under threat, and the very real risk that traditional ways of making food are being forgotten, or the ingredients used to prepare them dying out as more land is given away to growing global monocultures or lost to climate change. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Saladino is great at emphasising that nothing is set in stone, and if we start to care about food and its associated cultures more, then a lot can still be saved and built upon. Examples of this are the recent commercial success of Georgian Qveri wine, the re-cultivation of bere barley on Orkney by Barony Mills, and the resurrection of the alb lentil after more than thirty years from a seed discovered in the collection of the Vavilov institute in St Petersburg.

Saving and preserving food cultures is not a new fight, and Saladino makes this most clear when writing about seed banks – particularly the Vavilov Institute. Founded in the 20th century by the agronomist NIkolai Vavilov, this was the world’s first seed bank. Like many Soviet scientists, Vavilov did not survive Stalin’s purges, but the seed bank that bore his name was guarded by his students throughout the almost three-year-long siege of St Petersburg in WW2. After the siege, one of those students was found dead from starvation in a room full of rice. They had given their life rather than remove anything from the seed bank’s collection. It is in memory of people like this that we cannot give up.