A story about pickled ginger, food colouring and whether imitation is a form of culinary flattery or trickery.

I have recently got very into making pickles at home. There’s a real satisfaction in opening the fridge and seeing an array of Kilner Jars filled with various fruits, vegetables or meats (if you’ve never had a meat pickle, try it) pickling in mixtures of vinegar, spices and sugar.

Pickles are rarely difficult to make, they last for ages and give you immediate access to different strong flavours – either as a quick snack or an accompaniment that adds variety to a meal. They can be sweet, tangy, or wonderfully sour. Most of my recent pickles have been of the former two categories, so I was delighted to stumble across an incredibly simple recipe for beni shoga (red pickled ginger) in Emiko Davies’ fantastic book Gohan: Everyday Japanese Cooking – which promised to give a deep salty and sour flavour.

Anyone who has been to a sushi restaurant will be familiar with beni shoga: it is the red pickled ginger which is almost always served alongside maki rolls, nigiri or sashimi. Or I thought I was familiar with beni shoga in this way, until I tried to make it and realised it’s quite possible I’d never tried the real thing…

What is umesu?

Davies’ recipe for beni shoga is on the face of it the simplest recipe you could imagine. It has two ingredients: ginger (no surprise there) and umesu, otherwise known as ume plum vinegar. Trying to get my hands on some umesu is where my voyage of discovery began.

Umesu is the very (I would go far as saying aggressively) salty liquid that is the by-product from making Japanese pickled plums (umeboshi). It is not to be confused with umeshu, although English-speaking Google appears to do so, which is an alcoholic drink similarly made from ume plums, but which is significantly sweeter. To make umesu, the briny liquid is combined with red shiso leaves, giving the vinegar its red colouring, and it is this colour which dyes the ginger in the pickling process to make beni shoga.

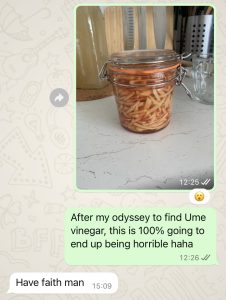

The other thing you need to know about umesu if you, like me, live in London is this: it is frustratingly hard to get your hands on. After visiting four different Asian supermarkets and coming up empty-handed, the only place I could find the stuff on sale was in Whole Foods. And, needless to say, it was as expensive as you might imagine ume plum vinegar from Whole Foods would be.

However, after having spent more than an hour cycling around different shops, it was my only option and I was, to use a poker-related expression, fairly pot committed. I put a couple of small bottles in my bag and headed home. While frustrating, this had given me some time to think: why is umesu was so hard to find if it’s such a commonly used ingredient for making red pickled ginger?

Fake it rather than make it

A quick bit of research revealed the answer to me: rather than using umesu to make beni shoga, it is a common practice to pickle the ginger using other vinegars and then add red food colouring to make it look like the real thing. This is the reason why a lot of beni shoga you will see (at least in the UK) whether in a restaurant or bought in a shop has a very bright, almost neon pink colour.

The beni shoga I made at home with my hard-found umesu is a much ruddier colour, more red/purple than pink, and the matchsticks of ginger are similarly paler and darker than the red pickled ginger I had previously been used to.

It also has a distinctly different and more complex taste. As mentioned above umeshu is incredibly salty and sour, and this balances nicely against the spicy sweetness of the ginger (which is blanched for a minute before pickling). It’s delicious and works brilliantly as a palette cleanser.

This was a pleasant surprise, as I have to admit I was unsure how it would taste initially. Having tasted some of the umesu “neat” before putting the ginger in, there was a part of me that thought my expensive pickling experiment might simply produce something a little too far along the “sour” spectrum for me to be able to handle.

Taste-wise my home-made beni shoga definitely has a much deeper salty/sour taste than the store-bought variety which uses red food colouring. While the taste of the ginger is still present it’s more ‘behind’ the saltiness giving variety rather than leading with a gingery kick. It is also, unsurprisingly, completely different to pickled ginger made with rice vinegar and sugar (gari), which has a much lighter and sweet taste. I find it nice to have a jar of each in the fridge to have access to both flavour profiles.

It seems from looking around at various ingredient lists on commercially produced red pickled ginger (as all the cool kids spend their time doing) that what will be bought and served in the UK under then name beni shoga most commonly will be some variety of this sweeter pickled ginger, but containing less sugar and with the addition of red food colouring. It still tastes different and has some of “real” beni shoga’s palette cleansing qualities, but it’s an imitation and not the real thing.

So what?

This is the first question that comes to my mind when thinking about this. Who actually cares? If the stuff is nice, people enjoy eating it, and by and large nobody notices or minds, what’s wrong with using food colouring instead of umesu when making beni shoga?

I would actually say nothing at all. Food is about what tastes good, not having to always follow tradition. There are no doubt practical reasons too; for instance, if the prices in the Whole Foods vinegar aisle are anything to go by then making “the real thing” might cause pickled ginger hyperinflation. Or maybe it’s simply that not enough umeboshi are pickled to produce the amount of vinegar that would be needed in order to supply Japanese restaurants across the world. Overall it doesn’t matter if people are satisfied with the status quo.

A similar phenomenon occurs in almost every chip shop in the UK, with people grabbing a bottle of “vinegar” and in fact covering their chips in non-brewed condiment. The taste of this watered down ethanoic acid (dyed brown with food colouring) imitates malt vinegar, and customers don’t seem to mind.

So, while “so what?” is the first question that comes to mind in relation to the use of food colouring, it’s not as interesting as the second: if you’re not using umesu, why bother to dye the ginger red at all?

The sincerest form of flattery

I think that what lies behind the saying “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery” is that the very act of imitation demonstrates that there is something worth imitating. In the case of beni shoga, the fact that restaurants or industrial producers will add red food colouring seems to be a nod to the fact that the real thing is delicious and a desirable thing to serve.

This also brings to mind another staple that will be found on any plate of sushi: wasabi. It is well known that (at least in the West) you’re very unlikely to have ever had real wasabi – with most commercially available pastes called wasabi being made mostly of mashed up horseradish which is later dyed green with food colouring to imitate the colour of freshly grated wasabi root.

There could also be something psychological going on here, with the addition of colour helping trick our brains into tasting what we’re expecting to taste (more bitter pickled ginger in the case of beni shoga, and a spicy and earthy kick from wasabi). There is also the aesthetic importance of what we expect to see with any particular meal. Perhaps it’s just me, but I think white “wasabi” would simply look wrong.

A similar phenomenon can also be seen in British Indian cuisine. In both chicken tikka masala and tandoori chicken, it’s commonplace to add red food colouring to give the dishes their distinctive colour (and no doubt make the dishes look spicier than they may actually be). In fact in the early 00s this was found to be so liberally used in chicken tikka masala that posed health risks. Tandoori chicken is defined by its cooking process and use of red kashmiri chilli powder, and the vibrant red colour this produces is now commonly supplemented with red food colouring.

This opens up more questions about the extent to which the presentation of food is as important as its flavour, and about the whole concept of “authenticity” when cooking different cuisines more generally. I’m not an authority on Japanese or Indian cuisine, but it’s certainly been an interesting rabbit hole to fall down.

And to think this whole train of thought started when I tried to make a simple pickle recipe. A recipe which, I remind you dear reader, had only two ingredients.

Recipes mentioned

- Beni shoga (Gohan: Everyday Japanese Cooking p.36)

- Gari (Gohan: Everyday Japanese Cooking p.35)