A powerful case for playing with your food, taking joy in the small things and eating in unusual environments.

“Oil paintings on canvas may look nice, but do they taste like chocolate?” This question was posed by London-based artist Annie Lee as part of an online exhibition with the Barbican in 2021, and forms a key part of a running theme through their work: the everyday joy that food can bring into our lives.

Annie has recently graduated from the Slade School of Fine Art, and for their final degree show they created a restaurant space within the gallery itself, with the playful title Life is like soup and I am a fork. I caught up with Annie to talk about this exhibition, the role that food plays in their work more generally and why they often focus on what we eat in their creative practice.

A fake restaurant that serves real food

In their own words, Annie describes Life is like soup and I am a fork as “a work on three levels, 1) an installation, 2) a functional restaurant, 3) an interactive performance-play. With elements of silliness and sincerity together, the work explores awkwardness, otherness, and belonging in the context of a social and public space.”

The work took the form of a small restaurant created in one of the exhibition spaces at the Slade, “with (doctored) awards and accolades to remind all visitors how accomplished the restaurant team were, handmade ceramics and tablecloths to create a warm and welcoming dining space, and a makeshift kitchen in the corner.”

Given the location of this space within the context of an art gallery, visitors tended to interact with the work firstly as an installation – but for Annie the central focus was the kitchen: “This was where the work came alive, the ‘restaurant’ was transformed into a functional serving space, activated by the people who come to visit each day to taste the food which was both cooked and served by me.”

The menu consisted of bread, soup and cake which changed daily. Annie tells me that the food was always vegan, and made fresh so the smells of onion, garlic and warm bread filled the room and outer corridor. “The main soup that I made was a Chinese ABC soup with vegetables simmered in coconut milk and miso, with the most popular accompanying bread being a caramelised onion loaf. The cakes included apple and cinnamon, strawberry and lemon, and carrot and cashew combinations – which I had developed over the course of my final year when my friends and I needed a pick-me-up (or an excuse to rest and eat) in the studios.” As part of the work, Annie would also pose as a waiter and deliver a short speech about the importance of the soup’s name to the chef (also Annie) as someone who had grown up in a British-born Chinese household.

“Food holds so much power in quickly creating connections and opening up conversations,” Continues Annie as they discuss the menu. “I was surprised at how easily strangers felt comfortable to sit at a table and meet others (and even share crockery when I was running low). I was also shown kindness and care when people donated their cooking equipment before the show, and during the show they helped me clean up – which is something I am very grateful for! For me, whilst the work is wrapped up in food and humour, everything around it is just as important – a collective community atmosphere, the conversations, and the sense of care.”

This connection between food and a caring community is central to Annie’s artistic practice and a pivotal part of this exhibition: “Accessibility and care are at the core of my approach to making art, and it was lovely to be able to provide this space for people and also talk with them about all sorts of things – from the cultural history of the food I was serving, their own relationship with cooking, and general life chats.”

Interactivity and humour

Life is like soup and I am a fork explored not only the pleasant experience of restaurant dining, but also some of the more awkward moments to which we are all accustomed. “Across the course of the exhibition, there were showings of a performance-play, which involved audience members observing and becoming performers themselves. Diners were led through a series of awkward scenarios, such as struggling to get into a tightly packed chair or humiliating one diner with a surprise birthday cake in a loud group singalong with backing tracks, disco lights, and paparazzi.”

Reflecting on this Annie continues, “Interactivity in art exhibitions can often be risky, because you don’t know how the public will react and you relinquish control of parts of the work in this way. However, I found this made every service and every performance uniquely magical. For example, in one of the performances, we just so happened to have a musician with their violin in the room, which made the singalong of Happy Birthday all the more special, their strings made an over-the-top addition to an already unnecessarily grandiose experience.”

“Contributions from other visitors also helped amplify the humour of the work, such as them leaving post-it note messages at the till in my absence, reviewing their experience on an actual TripAdvisor page for the Restaurant, or leaving a range of ‘tips’ in the tip jar. I will always remember checking this jar at the end of one day and seeing someone had tipped a ‘find support’ mental health resource card – which kind of weirdly encompasses some sort of essence of Life is like soup and I am a fork.”

Unpretentious joy

What I love about Annie’s work is the complete lack of pretention. What comes through most often is a playful relationship to food, which draws you in with charm before opening up deeper questions. I find that Annie’s work makes me chuckle, and then it makes me think.

A great example of this is their piece Rolling Pin for Parent and Child (with vegan ‘char siu’ bao on the side). This piece centres one of the most banal pieces of cooking equipment, a wooden rolling pin, as representative of the connections that can be found by cooking together; in this case making vegan dumplings with their mum. The dumplings look delicious, but they are the side-show, simply the food that has been created through the “hands, memories, family, talking, and time” that flow through the rolling pin.

Talking about this work, Annie said: “I was learning how to turn wood on the wooden lathe at the time and had always wanted to make my own rolling pin, so this was perfect. In my practice, I am interested in taking mundane objects and situations and subverting them in some way, so in this piece I made the handles of the rolling pin asymmetrically. One large end for the parent, and the other small end for the child. The idea is for two people to hold it together, only one hand on either end, to roll out the dough. It’s a bit like those teambuilding games that no one ever wants to do, but at least at the end of this one you get food!”

“The action is harder than you think, and you have to communicate and coordinate with the other person due to the uneven weight distribution and not having full control. However, I think this more playful experience of cooking together that is enabled by the oddly made object offers important conversations on navigating familial relationships.”

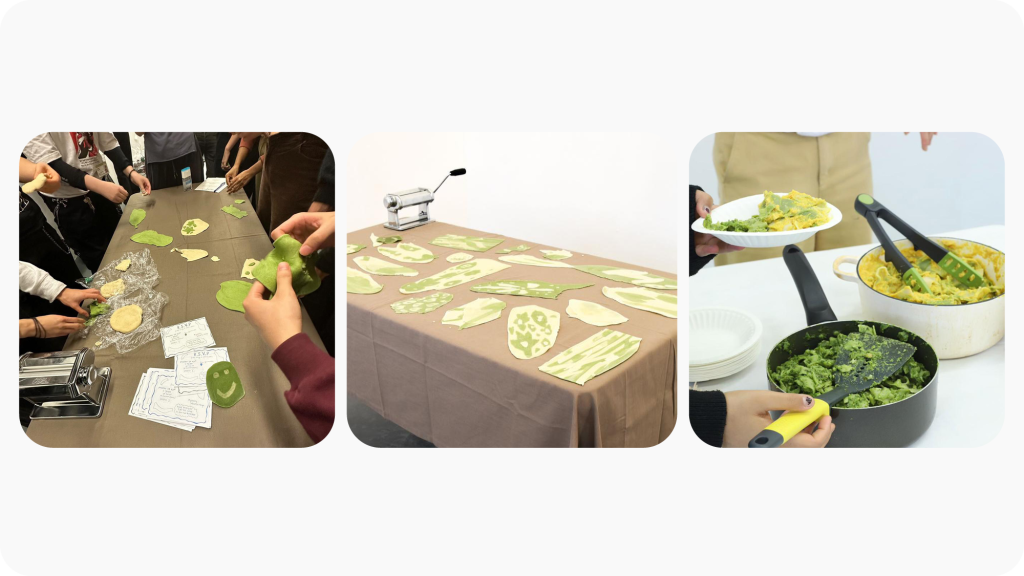

A similar exploration of this communal aspect of food extends into Annie’s friendships in the 2023 piece Pasta Party. Participants in this work were encouraged to create different patterns in pasta dough, and to treat the food they were making in the same way they might approach a canvas – before sitting down to enjoy the fruits of their labour together.

The piece was created as part of – and in many ways a rebuke to – a ‘crit’ during Annie’s time at the Slade School of Fine Art (an exercise where students present work for feedback from other students and tutors): “I always found the traditional crits at art school hard to engage in. Think ‘student puts a painting on a wall inspired by ‘the metaphysical’ and ‘liminality’ and you have no idea what to say or think and you spend the 30 minutes wondering what you can comment that will sound clever and pretentious enough to match everyone else who seems to know what they’re talking about’. This has happened way too many times and is the situation I wish to avoid at all costs for my own work!”

As such Pasta Party aimed to be as far away from over-intellectualised, inaccessibly abstract concepts as possible, and to focus instead on questions relating to how we actually live our lives: “Why can’t we just make and eat pasta and have fun? Why do we feel the pressure to speak and behave in a certain way as we enter supposedly formal spaces? Having enjoyed doing workshop facilitation in the past, I wanted to offer a similar hands-on activity that would engage people and open up conversations on what counts as ‘legitimate’ art.”

“I also wanted to make the work extend beyond the half hour time slot, so I cooked all this pasta and served it with homemade sauces a few days later, for it to be enjoyed as a communal meal. By this time, the conversations weren’t a forced analysis on the execution or process of making my art, but it was a gathering space that offered a chance for everyone to catch up on people’s days, or be nourished with lunch instead of getting the same old Tesco meal deal.”

Looking out for “spontaneous occurrences”

Annie’s joyful appreciation of food continues back through their earlier work as part of the Barbican’s 2021 exhibition It All Comes Down. As part of this exhibition, which was presented online during the Covid lockdowns, Annie collected images of everyday things to capture their “interactions and experiences of life at home.”

“Whilst the reason behind having to go into lockdown was awful, being forced to remain inside and not socialise actually allowed me to properly rest, which I hadn’t let myself do in ages. Going from a fast-paced schedule of new workshops and lectures every day to virtually nothing, I found joy in playing with my food and noticing interesting marks and surfaces on windows or tiles.

The central role played by food in these images can be best seen in Annie’s trio of “accidental food paintings” (my favourite of which being the toad in the hole transformed into a brick by an overly hot oven), and a Van Gough-style tree drawn into the bottom of a bowl of Rocky Road mix.

“When everything is the same everyday, these small moments of finding or making ‘paintings’ in things you wouldn’t normally consider art added a bit of variety into my daily routine. They enabled me to feel creative without having to put in painstaking effort and labour, which I think is a common misconception of what validates something as ‘art’.”

Speaking about the accidental food paintings, Annie said, “They were initially private moments between myself (and maybe my family when I forced them to look at my smiley faces), but over time they formed a collection of photographs shown in the exhibition that documented a very surreal time for everyone.”

An attitude to live by

Talking to Annie about their work was a great experience for me. It’s these sorts of interactions that you get through home cooking, and the connection and community that food can bring that made me want to start Watching the Pot in the first place, and Annie’s work puts this message across with an infectious charm.

I can’t wait to see what culinary creations come from them next, and I definitely have a new appreciation of the playful joy that food can bring into everyday life.

To find out more about Annie’s work, check out their website and Instagram.